Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec French, 1864-1901

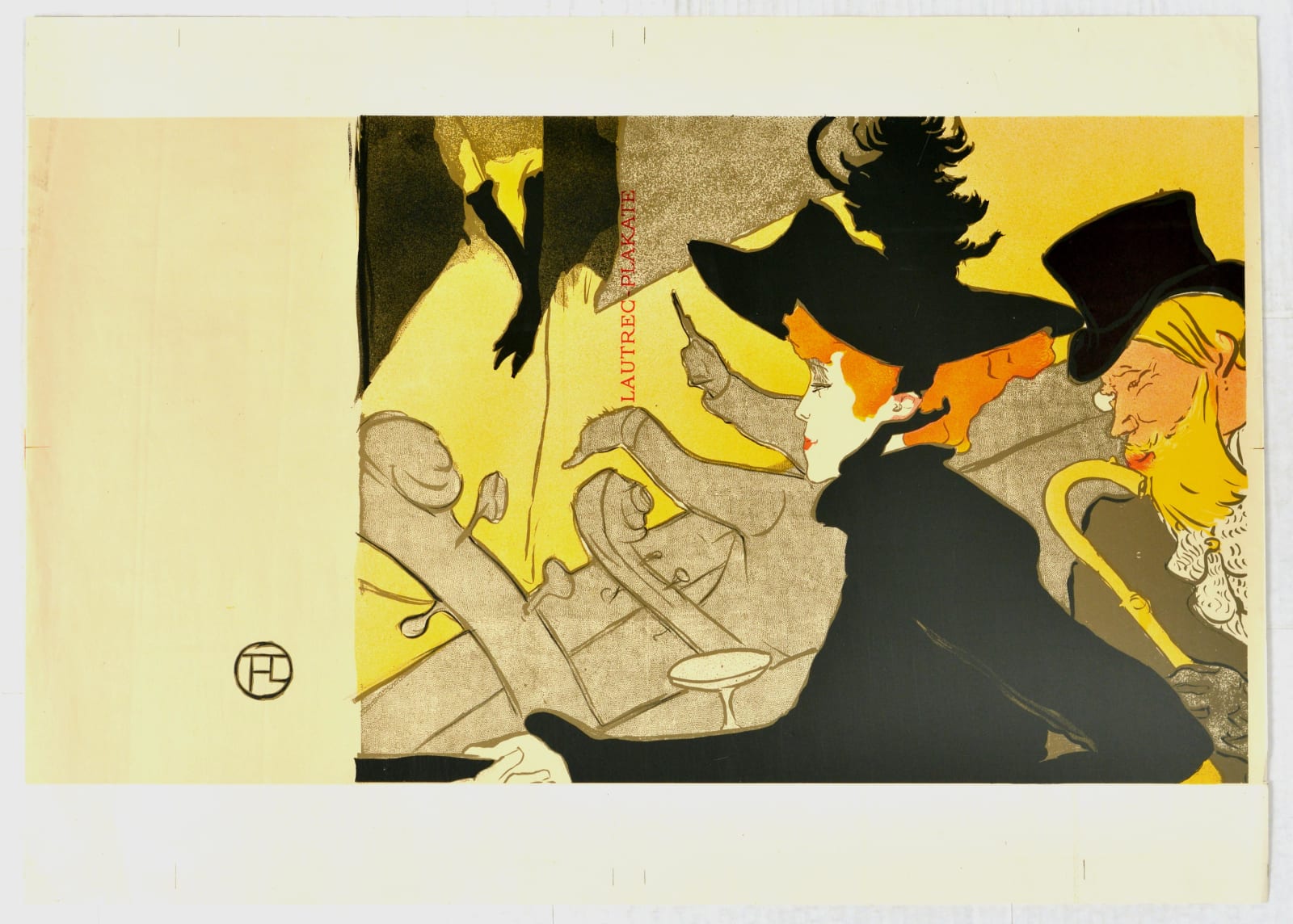

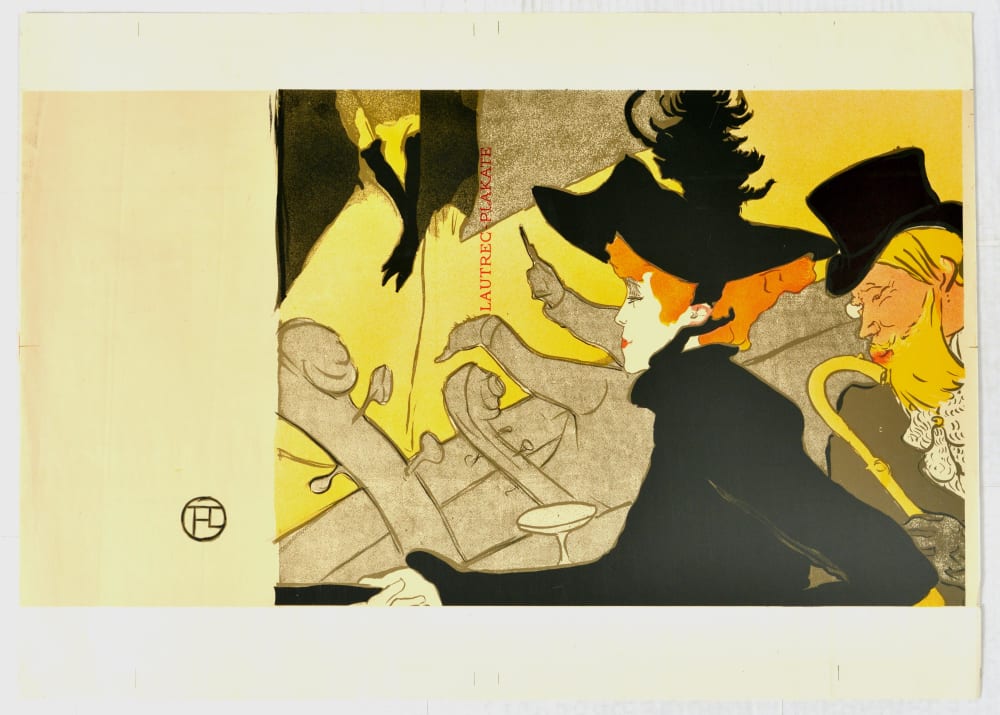

Divan Japonais

Lithograph

Size without frame 22 x 31 ins

£ 475.00

In 1899 Henri, Vicomte de Toulouse-Lautrec, was taken into a mental home, at the age of 34. Two years later, worn out with dissolution and drink, he died at the age of 36, like his colleague Van Gogh. The story behind these few tragic years of life is one of self-destruction and the achievement of genius.

Born into one of the most ancient noble families of France, Lautrec seemed destined to follow its traditional way of living, when two accidents following within a short time of each other arrested the growth of his legs, and dramatically changed his life. The crippled, stunted boy of 15, with a passion for sketching grew into a grotesque dwarf who flung himself into a life of excess, burning himself out in the dance halls, brothels and cabarets of Montmartre and finally, as he himself admitted, 'committing moral suicide'. Montmartre was not slow in taking to itself this aristocratic 'little monster' whose buffoonery, depravity and wit brought him the sort of eccentric popularity, without pity or mockery, which he knew he could not obtain elsewhere. Out of it all there emerged the remarkable artist we know, who captured with penetrating clarity the excitement and decadence of an epoch which was finally to destroy him.

I quote at length Arthur Huc's editorial, as editor of La Dépêche de Toulouse, writing in 1899 and quoted in Julia Frey's superb biography of Lautrec (London 1994): 'in this malformed body lived an impulsive, agile mind, remarkably receptive to all aspects of art. Of all the painters I have known, he was certainly one of the most intellectual: well read without pretending to be literary, subtle as amber and tough as only a Parisian can be. I can't find a different word to describe his talent, and he himself would certainly not have wanted another. He was brutally cynical .. and he wished to be, in both his life and his painting. He has been criticized for his excesses. It's true that he was nocturnal, loved to frequent low dives and was hardly an enemy of potent spirits. But who is to say that for him this was not a form of agreeable suicide, an ingenious way of quickly shaking off that dusty cloak of flesh which must have been such a burden to him? "I can paint until I'm forty", he said to me one day. "After that, I intend to dry up". In fact, he did everything he could to finish himself off.

He loved staying out all night, and, a curious detail, this gnome, who seemed designed to frighten off love .. was not too often rejected. No doubt, it is exactly such overindulgences which drove poor Lautrec to the asylum. But this excessive behaviour was inextricably mixed with his talent. Both came from the same source: they were a reaction to the bizarre accidents of Nature, which sometimes lodges the mind of an imbecile in the body of a Greek god and a delicate spirit in a deformed shell.'

[Frey}: Huc went on to say that he thought Henri's originality as an artist came largely from his use of ugliness and exaggeration of physical quirks to reveal the psychological truths of his models, to bring forth, albeit with cruelty, the irony of the antagonism between interior and exterior beauty. He pointed out that the acuity of Henri's vision came from his ability to penetrate people's masks, to get to the 'warts and blemishes' of their characters, and from his refusal to compromise or make pretty pictures. All his portraits, even those of friends, observed Huc, were marked by his insistent portrayal of sometimes brutal truths.

He concluded by wishing, as both friend and admirer, that Henri would be back to painting soon [after his stay in the asylum], remarking prophetically: 'his works are already numerous. Even if he were to disappear forever right now, what he leaves behind is enough to assure him one of the most important places in the artistic movement of recent years, for Lautrec has been the most living painter of our decadent age'. Huc, alone of Henri's contemporaries, foresaw the permanence of his impact as an artist.

Between 1882 and 1892 the Café du Divan Japonais, at 75 rue des Martyrs, had been run first by the grocer and poet Jehan Sarrazin and then by the eccentric Maxime Lisbonne. In 1893 it was transformed into a 'café-concert' by Edouard Fournier, whose name appears on the original poster. The auditorium was decorated with lanterns and bamboo chairs in Japanese style; 'Japonisme' had enjoyed a great vogue ever since the 1860s; collectors pursued Japanese prints, and the Goncourt brothers and Philippe Burty extolled the Japanese aesthetic. Lautrec, who was asked to design the poster for the opening of the Divan Japonais, decided to adopt Japanese principles of composition, cropping and colour.

This is an original vintage printer's proof of a dust jacket for a book Lautrec-Plakate featuring art from an advertising poster by Toulouse-Lautrec, taken from his famous design of the lithograph entitled 'Divan Japonais', printed in 1893. The original poster depicts three people from the Montmartre of Toulouse-Lautrec's time; the dancer is Jane Avril, one of Lautrec's famous muses, and beside her is the writer Édouard Dujardin. Beyond is the stage with, on the left, the figure of Yvette Guilbert, half concealed by the curtain and identifiable only by her black gloves; Lautrec has coolly left out her head as if to focus the viewer's attention on Jane Avril alone. This dust jacket proof dates from the 1960s.

Born into one of the most ancient noble families of France, Lautrec seemed destined to follow its traditional way of living, when two accidents following within a short time of each other arrested the growth of his legs, and dramatically changed his life. The crippled, stunted boy of 15, with a passion for sketching grew into a grotesque dwarf who flung himself into a life of excess, burning himself out in the dance halls, brothels and cabarets of Montmartre and finally, as he himself admitted, 'committing moral suicide'. Montmartre was not slow in taking to itself this aristocratic 'little monster' whose buffoonery, depravity and wit brought him the sort of eccentric popularity, without pity or mockery, which he knew he could not obtain elsewhere. Out of it all there emerged the remarkable artist we know, who captured with penetrating clarity the excitement and decadence of an epoch which was finally to destroy him.

I quote at length Arthur Huc's editorial, as editor of La Dépêche de Toulouse, writing in 1899 and quoted in Julia Frey's superb biography of Lautrec (London 1994): 'in this malformed body lived an impulsive, agile mind, remarkably receptive to all aspects of art. Of all the painters I have known, he was certainly one of the most intellectual: well read without pretending to be literary, subtle as amber and tough as only a Parisian can be. I can't find a different word to describe his talent, and he himself would certainly not have wanted another. He was brutally cynical .. and he wished to be, in both his life and his painting. He has been criticized for his excesses. It's true that he was nocturnal, loved to frequent low dives and was hardly an enemy of potent spirits. But who is to say that for him this was not a form of agreeable suicide, an ingenious way of quickly shaking off that dusty cloak of flesh which must have been such a burden to him? "I can paint until I'm forty", he said to me one day. "After that, I intend to dry up". In fact, he did everything he could to finish himself off.

He loved staying out all night, and, a curious detail, this gnome, who seemed designed to frighten off love .. was not too often rejected. No doubt, it is exactly such overindulgences which drove poor Lautrec to the asylum. But this excessive behaviour was inextricably mixed with his talent. Both came from the same source: they were a reaction to the bizarre accidents of Nature, which sometimes lodges the mind of an imbecile in the body of a Greek god and a delicate spirit in a deformed shell.'

[Frey}: Huc went on to say that he thought Henri's originality as an artist came largely from his use of ugliness and exaggeration of physical quirks to reveal the psychological truths of his models, to bring forth, albeit with cruelty, the irony of the antagonism between interior and exterior beauty. He pointed out that the acuity of Henri's vision came from his ability to penetrate people's masks, to get to the 'warts and blemishes' of their characters, and from his refusal to compromise or make pretty pictures. All his portraits, even those of friends, observed Huc, were marked by his insistent portrayal of sometimes brutal truths.

He concluded by wishing, as both friend and admirer, that Henri would be back to painting soon [after his stay in the asylum], remarking prophetically: 'his works are already numerous. Even if he were to disappear forever right now, what he leaves behind is enough to assure him one of the most important places in the artistic movement of recent years, for Lautrec has been the most living painter of our decadent age'. Huc, alone of Henri's contemporaries, foresaw the permanence of his impact as an artist.

Between 1882 and 1892 the Café du Divan Japonais, at 75 rue des Martyrs, had been run first by the grocer and poet Jehan Sarrazin and then by the eccentric Maxime Lisbonne. In 1893 it was transformed into a 'café-concert' by Edouard Fournier, whose name appears on the original poster. The auditorium was decorated with lanterns and bamboo chairs in Japanese style; 'Japonisme' had enjoyed a great vogue ever since the 1860s; collectors pursued Japanese prints, and the Goncourt brothers and Philippe Burty extolled the Japanese aesthetic. Lautrec, who was asked to design the poster for the opening of the Divan Japonais, decided to adopt Japanese principles of composition, cropping and colour.

This is an original vintage printer's proof of a dust jacket for a book Lautrec-Plakate featuring art from an advertising poster by Toulouse-Lautrec, taken from his famous design of the lithograph entitled 'Divan Japonais', printed in 1893. The original poster depicts three people from the Montmartre of Toulouse-Lautrec's time; the dancer is Jane Avril, one of Lautrec's famous muses, and beside her is the writer Édouard Dujardin. Beyond is the stage with, on the left, the figure of Yvette Guilbert, half concealed by the curtain and identifiable only by her black gloves; Lautrec has coolly left out her head as if to focus the viewer's attention on Jane Avril alone. This dust jacket proof dates from the 1960s.

Join our mailing list

McEwan Gallery Newsletter

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.